Svartelfheim

This challenge was pretty fun and was a great opportunity to learn more about ELF files. It was part of the difficult reverse challenges of FCSC 2024.

First run

We are given a single ELF file. Let’s execute it :

$ ./svartalfheim

Welcome to Svartalfheim

It seems that the program waits for user input before continuing, let’s try with a fake password :

password

Nope

That’s all… Not much to deal with. Let’s analyze this binary under the microscope.

The analysis begins

The challenge is fairly minimal at first sight : a single EXEC ELF file with no sections and no symbols :

$ readelf -h svartalfheim

ELF Header:

Magic: 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

Class: ELF64

Data: 2's complement, little endian

Version: 1 (current)

OS/ABI: UNIX - System V

ABI Version: 0

Type: EXEC (Executable file)

Machine: Advanced Micro Devices X86-64

Version: 0x1

Entry point address: 0x41000

Start of program headers: 64 (bytes into file)

Start of section headers: 0 (bytes into file)

Flags: 0x0

Size of this header: 64 (bytes)

Size of program headers: 56 (bytes)

Number of program headers: 9

Size of section headers: 64 (bytes)

Number of section headers: 0

Section header string table index: 0

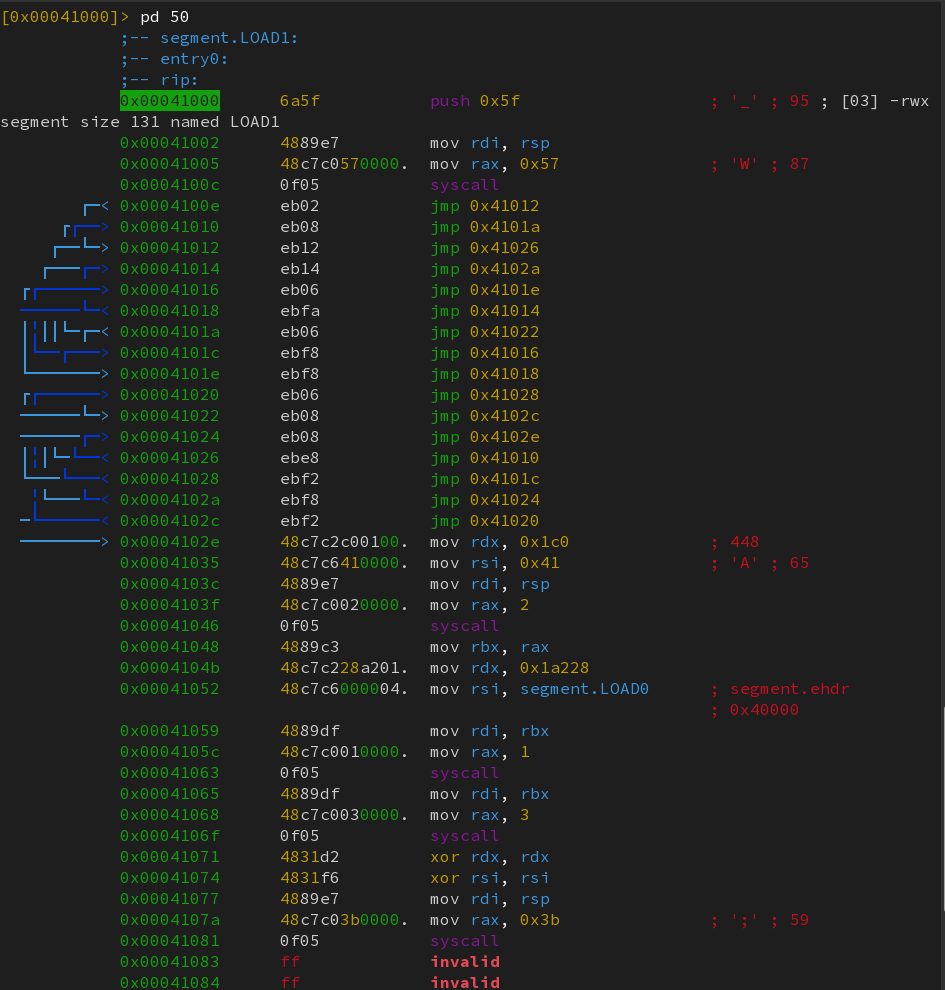

Using radare2, it can be seen that there are less than 50 instructions in the entire binary :

The following C code roughly summarizes what is happening :

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#define SEGMENT0 0x40000

#define FILE_SZ 0x1a228

int main(void) {

unlink("_");

int fd = open("_", O_WRONLY | O_CREAT, S_IRWXU);

write(fd, SEGMENT0, FILE_SZ);

close(fd);

execve("_", NULL, NULL);

}

Basically, all this does is that it dumps the entire program in memory (which happens to be of same size as the original ELF file) into the file _, and then executes it. But wait, this should result in an infinite loop, shouldn’t it ? How is even printed the string Welcome to svartalfheim ? Let’s search for strings :

$ strings svartalfheim

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2

!"#$%&'()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]^_`abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz{|}~

! #"%$'&)(+*-,/.1032547698;:=<?>A@CBEDGFIHKJMLONQPSRUTWVYX[Z]\_^a`cbedgfihkjmlonqpsrutwvyx{z}|

"# !&'$%*+()./,-23016745:;89>?<=BC@AFGDEJKHINOLMRSPQVWTUZ[XY^_\]bc`afgdejkhinolmrspqvwtuz{xy~

#"! '&%$+*)(/.-,32107654;:98?>=<CBA@GFEDKJIHONMLSRQPWVUT[ZYX_^]\cba`gfedkjihonmlsrqpwvut{zyx

....

|}z{xyvwturspqnolmjkhifgdebc`a^_\]Z[XYVWTURSPQNOLMJKHIFGDEBC@A>?<=:;8967452301./,-*+()&'$%"# !

~}|{zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcba`_^]\[ZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA@?>=<;:9876543210/.-,+*)('&%$#"!

e RF

mSZh9rM

No sign of this string anywhere. Only weird stuff. There is definitely some black magic happening here…

The hidden machinery : ld.so

The only way this can be happening is that some instructions are executed before the entrypoint is even reached. You actually probably already know this : your ELF file is not directly executed on its own. Instead, the dynamic loader (ld.so) takes care of loading the shared libraries and missing dependencies. From man ld.so :

The programs

ld.soandld-linux.sofind and load the shared objects (shared libraries) needed by a program, prepare the program to run, and then run it.

ELF files contain a special segment of type p_type = PT_INTERP that contains the path to the program interpreter (or dynamic loader) :

$ readelf -l svartalfheim -W | grep INTERP

INTERP 0x000238 0x0000000000040238 0x0000000000040238 0x00001c 0x00001c R 0x1

$ cat svartalfheim | tail -c +568 | head -c 28 | hexdump -C

00000000 00 2f 6c 69 62 36 34 2f 6c 64 2d 6c 69 6e 75 78 |./lib64/ld-linux|

00000010 2d 78 38 36 2d 36 34 2e 73 6f 2e 32 |-x86-64.so.2|

0000001c

Also, all DYN (shared libraries and PIE executables) and EXEC (non-relocatable binaries) ELF files that use dynamic libraries have a special segment of p_type = PT_DYNAMIC. If sections are present, this segment contains a single section called .dynamic. It contains informations required by the loader to properly work. This is probably where the magic happens, and it might be worth giving it a look. But first, let’s dump all the versions of _ so that we can properly understand what is happening.

_’s history

Dumping all versions

Using ptrace, it is pretty easy to intercept all execve syscalls to save all versions of the code. Here is a sample C code that does just that ( + checks there are no duplicates ) :

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/ptrace.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/user.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <syscall.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int intercept_execve(int child, int save) {

int status;

int syscall_nr;

int count = 0;

FILE *current_elf;

FILE *f;

FILE *sha_file;

char content[FILE_LEN];

char filename[64];

char hash[64];

char prev_hash[64];

struct user_regs_struct regs;

while (1) {

// Entering syscall

ptrace(PTRACE_SYSCALL, child, NULL, NULL);

if (!waitpid(child, &status, 0) || WIFEXITED(status))

return 0;

ptrace(PTRACE_GETREGS, child, NULL, ®s);

syscall_nr = regs.orig_rax;

// Execve

if (syscall_nr == 59) {

fprintf(stderr, "execve(%016x, %lld, %lld)", regs.rdi, regs.rsi, regs.rdx);

}

ptrace(PTRACE_SYSCALL, child, NULL, NULL);

if (!waitpid(child, &status, 0) || WIFEXITED(status))

return 0;

// Exiting execve syscall

if (syscall_nr == 59) {

current_elf = fopen("_", "rb");

if (current_elf) {

// Check if duplicate

sha_file = popen("sha256sum _", "r");

fread(hash, 64, 1, sha_file);

fclose(sha_file);

if (memcmp(hash, prev_hash, 64) != 0) {

snprintf(filename, 64, "versions/v%04d", count);

printf("New version : %s\n", filename);

fread(content, FILE_LEN, 1, current_elf);

fclose(current_elf);

f = fopen(filename, "wb");

fwrite(content, FILE_LEN, 1, f);

fclose(f);

memcpy(prev_hash, hash, 64);

count++;

} else {

fclose(current_elf);

}

}

}

}

}

Changes during the first step

Using this code, I managed to find 6793 different versions of the program (without counting the original binary, so 6794 actually). Let’s investigate what is the difference between the first two of them :

$ hexdump -C svartalfheim > hexdumps/0

$ hexdump -C versions/v0000 > hexdumps/1

$ diff hexdumps/0 hexdumps/1

56c56

< 00002040 07 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 e8 21 04 00 00 00 00 00 |.........!......|

---

> 00002040 07 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 30 37 04 00 00 00 00 00 |........07......|

58c58

< 00002060 08 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 30 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |........0.......|

---

> 00002060 08 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 60 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |........`.......|

So something is going on in the 0x2000s. In what program header is it ?

$ readelf -l svartalfheim -W

Elf file type is EXEC (Executable file)

Entry point 0x41000

There are 9 program headers, starting at offset 64

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr FileSiz MemSiz Flg Align

PHDR 0x000040 0x0000000000040040 0x0000000000040040 0x0001f8 0x0001f8 R 0x8

INTERP 0x000238 0x0000000000040238 0x0000000000040238 0x00001c 0x00001c R 0x1

[Requesting program interpreter: /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2]

LOAD 0x000000 0x0000000000040000 0x0000000000040000 0x000254 0x000254 R 0x1000

LOAD 0x001000 0x0000000000041000 0x0000000000041000 0x000083 0x000083 RWE 0x1000

LOAD 0x002000 0x0000000000042000 0x0000000000042000 0x000235 0x000235 RW 0x1000

DYNAMIC 0x000000 0x0000000000042000 0x0000000000042000 0x000000 0x000000 RW 0x1000

LOAD 0x003000 0x0000000000043000 0x0000000000043000 0x005dd0 0x005dd0 RW 0x1000

LOAD 0x009000 0x0000000000049000 0x0000000000049000 0x010178 0x010178 R 0x1000

LOAD 0x01a000 0x000000000005a000 0x000000000005a000 0x000228 0x000228 RW 0x1000

This falls in the DYNAMIC segment (which overlaps with the third segment of type LOAD) ! Something changed in the internal state of the loader. Now, enough random observations. Let’s dive into the inner mechanisms of ld.so.

PT_DYNAMIC program header

In the following, if you want, you can grab you own local copy of elf.h to follow along with me. On most linux distros, it is located under /usr/include/elf.h.

The DYNAMIC program header is an array of Elf64_Dyn elements :

typedef struct

{

Elf64_Sxword d_tag; /* Dynamic entry type */

union

{

Elf64_Xword d_val; /* Integer value */

Elf64_Addr d_ptr; /* Address value */

} d_un;

} Elf64_Dyn;

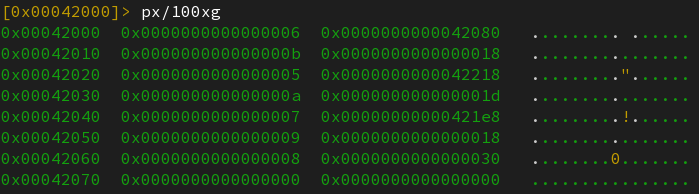

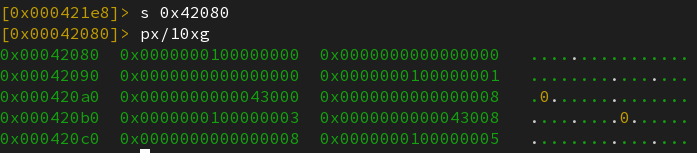

Let’s dump the content of this table with radare2 :

The corresponding entries are :

0x42000: entry of typeDT_SYMTAB: location of the symbol table.0x42010: entry of typeDT_SYMENT: the size of an entry in the symbol table (3 dwords).0x42020: entry of typeDT_STRTAB: location of the string table.0x42030: entry of typeDT_STRSZ: size of the string table.0x42040: entry of typeDT_RELA: location of the relocation with addend table.0x42050: entry of typeDT_RELAENT: size of one rela entry.0x42060: entry of typeDT_RELASZ: total size, in bytes, of the rela table.0x42070: entry of typeDT_NULL: indicates the end of the dynamic table.

Relocation table

We now understand what happens in the first step : the address of the relocation table was changed. The rela table is what holds the relocations with addend. A relocation specifies an address to be overwritten and maps it to a symbol : upon execution of the program, the loader replaces the content at this address with the symbol value. This is useful when using dynamic libraries, for example to access external symbols whose location is not known at compile time.

More formally, relocations with addend are described by the Elf64_Rela structure :

typedef struct

{

Elf64_Addr r_offset; /* Address */

Elf64_Xword r_info; /* Relocation type and symbol index */

Elf64_Sxword r_addend; /* Addend */

} Elf64_Rela;

(r_info holds two informations in a single qword : the type of relocation on the 4 lower bytes, and the symbol index in the symbol table on the 4 most significant bytes).

When ld.so reads the relocation table, it iterates over the relocation entry and overwrites with a specific value depending on the type of relocation. As you will see later, only 3 types are of interest for us. In the following, S denotes the value of the symbol and A the addend.

R_X86_64_64(=1) : effectively doing alea [addr], [S+A]R_X86_64_COPY(=5) : effectively doing amov [addr], [S]R_X86_64_RELATIVE(=8) : effectively doing amov [addr], A

For more details, I found those two resources pretty useful : https://intezer.com/blog/malware-analysis/executable-and-linkable-format-101-part-3-relocations/ and https://docs.oracle.com/cd/E23824_01/html/819-0690/chapter6-54839.html.

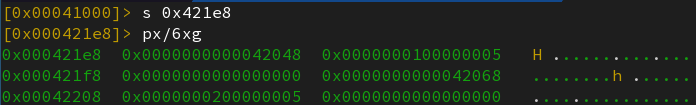

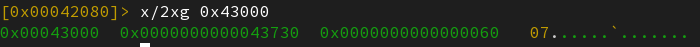

Again, let’s use radare2 to dump the relocation table of the initial program.

The program interpreter will thus be executing those two following instructions :

mov [0x42048], [value of sym1]

mov [0x42068], [value of sym2]

effectively replacing the relocation table and its size, as was previously noticed.

Symbol table

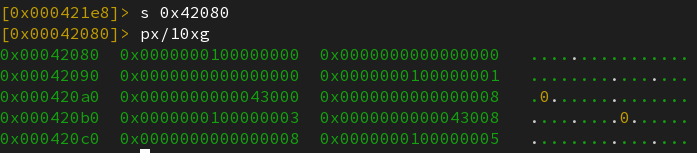

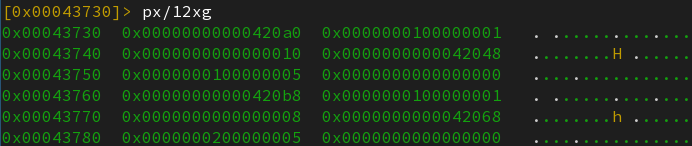

Now, what are the values of the symbols indexed by 1 and 2 ? For this, we need to take a look at the symbol table at 0x42080.

Each entry is an Elf64_Sym struct of 24 bytes :

typedef struct

{

Elf64_Word st_name; /* Symbol name (string tbl index) */

unsigned char st_info; /* Symbol type and binding */

unsigned char st_other; /* Symbol visibility */

Elf64_Section st_shndx; /* Section index */

Elf64_Addr st_value; /* Symbol value */

Elf64_Xword st_size; /* Symbol size */

} Elf64_Sym;

What is really of interest for us here is the st_value field : symbol 1 holds the value at address st_value=0x43000 (0x43730) and symbol 2 st_value=0x43008 (0x60).

And this explains the observed diff in the first two versions (here).

The next steps

Manually decoding the second step

Repeating the same process, let’s see what happens in the next step.

-

Relocation table :

-

Symbol table (does not change) :

-

Value of symbols (does not change):

Initially, 0x420a0 contains the address of the current relocation table (0x43000). The first executed instruction is

lea [0x420a0], [0x43000 + 0x10]

0x420a0 is the address at which is stored the value of the second symbol (index 1). So now, the value of this symbol is 0x43010. The next instruction then reads as

mov [0x42048], [0x43010]

which updates the location of the relocation table for the next time this binary is loaded by ld.so.

Then,

lea [0x420b8], [0x43010 + 0x8]

updates the value of the second symbol to 0x43018, and finally

mov [0x42068], [0x420b8]

updates the size of the relocation table for the next generation.

The hidden instruction pointer

I find it more intuitive to think about the previous instructions in terms of pointers :

*0x420a0 <- *0x420a0 + 0x10

*0x42048 <- **0x420a0

*0x420b8 <- *0x420a0 + 0x8

*0x42068 <- **0x420b8

Don’t forget : address 0x42048 holds the current relocation table, and 0x42068 holds its size. This starts to make sense : a relocation table is kind of a sequence of instructions, and 0x420a0 is like a instruction pointer (here a pointer in an array of relocation table pointers).

(Almost) every time the binary replicates itself, this pointer is incremented by 0x10. The first 8 bytes are the address of the next relocation table, and the next 8 bytes are its size. The only exception to this rule should happen when branching due to loops or conditions.

It can be seen in the next versions that all relocation tables look the same : some core relocations, followed by an update of the relocation table pointer and relocation table size.

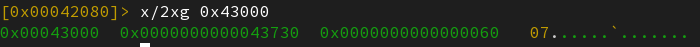

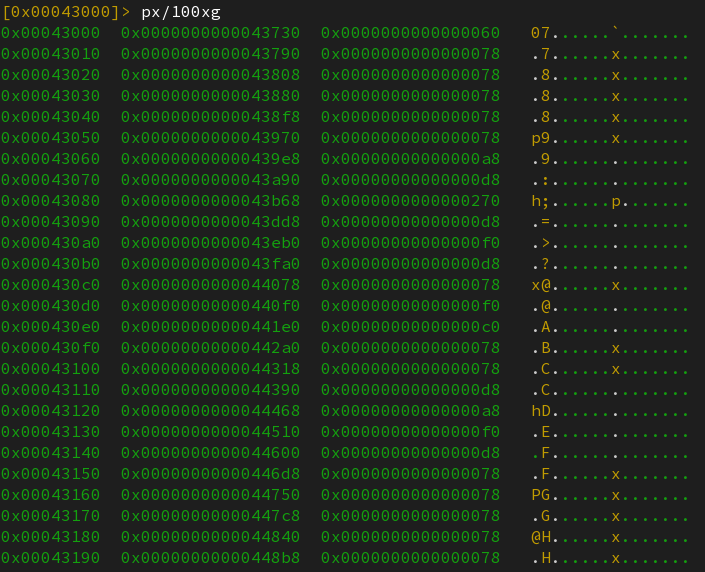

The relocation table pointer starts at 0x43000. To confirm our theory, let’s dump data in this region :

This indeed looks very much like an array of (ptr, size).

Dumping the hidden code

Now, let’s do a quick recap of the memory layout :

0x41000 -> 0x41083: code.0x42000 -> 0x42080: program interpreter informations.0x42080 -> 0x42210: symbol table.0x43000 -> 0x43730: array of relocation table pointers, along with their size.0x43730 -> ??? (far): relocation tables.

Let’s parse the relocations for every version in order to understand how the password is checked.

The parser

Since there are no sections in this ELF file, I used my own script to parse the relocation table. Most tools out there deal with sections, so maybe it was possible to artifically add sections for compatilibity with these tools. But considering that both addends and symbol values could be updated during the relocation process, I preferred to do it myself just to make sure the output was consistent.

from elftools.elf.elffile import ELFFile

WORD_MASK = 0xffffffff

BASE_ADDR = 0x40000

DT_SYMTAB = 6

DT_RELA = 7

DT_RELASZ = 8

RELA_ENT = 0x18

SYMTAB_ENT = 0x18

R_X86_64 = 1

R_X86_64_COPY = 5

R_X86_64_RELATIVE = 8

VERSIONS_COUNT = 6793

def parse_dynamic_segment(f):

"""

Parse PT_DYNAMIC segment to return the address of the symbol table,

the address and size of the rela table

"""

elf_file = ELFFile(f)

dynamic = elf_file.get_segment(5)

assert dynamic.header['p_type'] == 'PT_DYNAMIC'

dynamic_offset = dynamic.header['p_vaddr'] - BASE_ADDR

f.seek(dynamic_offset)

symtab, rela, relasz = 0, 0, 0

while True:

dt_entry = f.read(16) # structy Elf64_Dyn

if dt_entry == b'\x00' * 16: # end

break

type = int.from_bytes(dt_entry[:8], 'little')

val = int.from_bytes(dt_entry[8:], 'little')

if type == DT_SYMTAB:

symtab = val

elif type == DT_RELA:

rela = val

elif type == DT_RELASZ:

relasz = val

return symtab, rela, relasz

def parse_symtab(f, symtab, symtab_size):

"""

Parse symbol table.

Returns a list of triplets (address, name, initial value)

"""

ret = []

f.seek(symtab - BASE_ADDR)

for r in range(symtab, symtab+symtab_size, SYMTAB_ENT):

sym = f.read(SYMTAB_ENT)

name = int.from_bytes(sym[:4], 'little')

init_value = int.from_bytes(sym[8:16], 'little')

ret.append((r, name, init_value))

return ret

def parse_relocations(f, syms, rela, relasz):

"""

Returns :

+ an array of string repr of relocations

+ the initial addend values

"""

f.seek(rela - BASE_ADDR)

initial_addends = []

relocs = []

for r in range(rela, rela+relasz, RELA_ENT):

entry = f.read(RELA_ENT)

offset = int.from_bytes(entry[:8], 'little')

info = int.from_bytes(entry[8:16], 'little')

rel_type = info & WORD_MASK

rel_sym = info >> 32

initial_addends.append(int.from_bytes(entry[16:], 'little'))

if rel_type == R_X86_64:

relocs.append(f"*{offset:08x} <- *({syms[rel_sym][0]+8:08x}) + *{r+0x10:08x}")

elif rel_type == R_X86_64_COPY:

relocs.append(f"*{offset:08x} <- **({syms[rel_sym][0]+8:08x})")

elif rel_type == R_X86_64_RELATIVE:

relocs.append(f"*{offset:08x} <- *{r+0x10:08x}")

return (initial_addends, relocs)

def dump_all_relocations():

for i in range(VERSIONS_COUNT):

with open(f'versions/v{i:04d}', 'rb') as f:

symtab, rela, relasz = parse_dynamic_segment(f)

syms = parse_symtab(f, symtab, 15*SYMTAB_ENT) # 15 is arbitrary here

initial_addends, relocs = parse_relocations(f, syms, rela, relasz)

print("******")

print(f"Version {i:04d}")

print("******")

print("Initial symbol values :")

print('\n'.join(map(lambda x: f"{x[0]+0x8:08x}: {x[2]:08x}", syms)))

print("******")

print("Initial addend values :")

print('\n'.join([f"{rela+0x10+i*0x18:08x}: {initial_addends[i]:08x}" for i in range(len(initial_addends))]))

print("******")

print("Relocations :")

print('\n'.join(relocs))

print("******")

Here is a sample result :

******

Version 0000

******

Initial symbol values :

00042088: 00000000

000420a0: 00043000

000420b8: 00043008

000420d0: 00000000

000420e8: 00000000

00042100: 00000000

00042118: 00000000

00042130: 00000000

00042148: 00000000

00042160: 00000000

00042178: 00000000

00042190: 00000000

000421a8: 00000000

000421c0: 00000000

000421d8: 00000000

******

Initial addend values :

00043740: 00000010

00043758: 00000000

00043770: 00000008

00043788: 00000000

******

Relocations :

*000420a0 <- *(000420a0) + *00043740

*00042048 <- **(000420a0)

*000420b8 <- *(000420a0) + *00043770

*00042068 <- **(000420b8)

******

******

Version 0001

******

Initial symbol values :

00042088: 00000000

000420a0: 00043010

000420b8: 00043018

000420d0: 00000000

000420e8: 00000000

00042100: 00000000

00042118: 00000000

00042130: 00000000

00042148: 00000000

00042160: 00000000

00042178: 00000000

00042190: 00000000

000421a8: 00000000

000421c0: 00000000

000421d8: 00000000

******

Initial addend values :

000437a0: 000000ff

000437b8: 00000010

000437d0: 00000000

000437e8: 00000008

00043800: 00000000

******

Relocations :

*00042100 <- *000437a0

*000420a0 <- *(000420a0) + *000437b8

*00042048 <- **(000420a0)

*000420b8 <- *(000420a0) + *000437e8

*00042068 <- **(000420b8)

******

CFG for an invalid input

Let’s look at the relocation table pointer for each version. Three important observations can be made :

- It can be noticed that the relocation pointer lives in the interval

[0x43000, 0x43650], but the relocation table array extends far beyond that. This indicates that we have missed the branch that is taken on valid input. - We can expect that the main code is edited by relocations when asking for user input. We might have to look for relocations that affect addresses in the first segment.

- Third : we can expect a loop that checks our input passphrase.

Changes in the main code

Let’s first inspect modifications of the main code. For this, we search in relocations for the address 0x4100e, because the start of the obfuscated jumps at the beginning look like a placeholder for potentially future useful code.

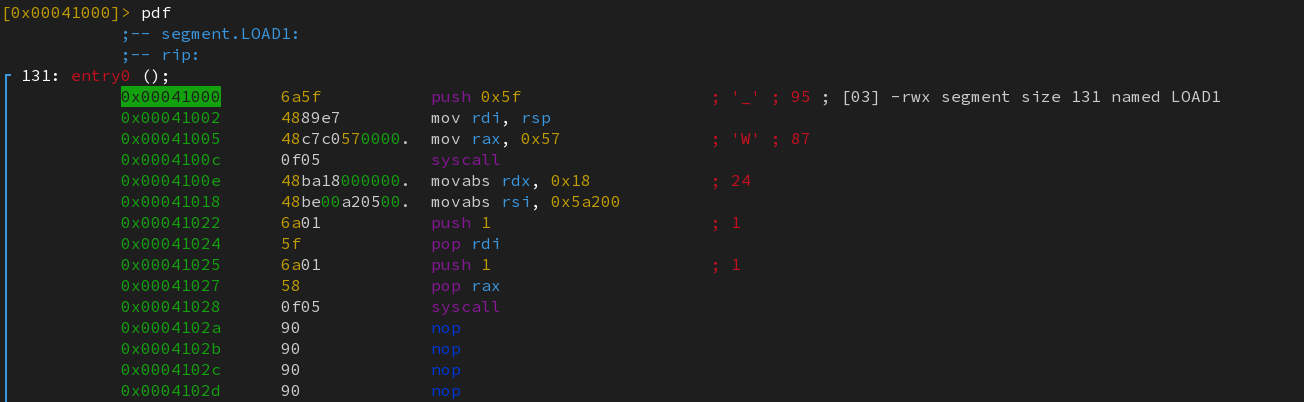

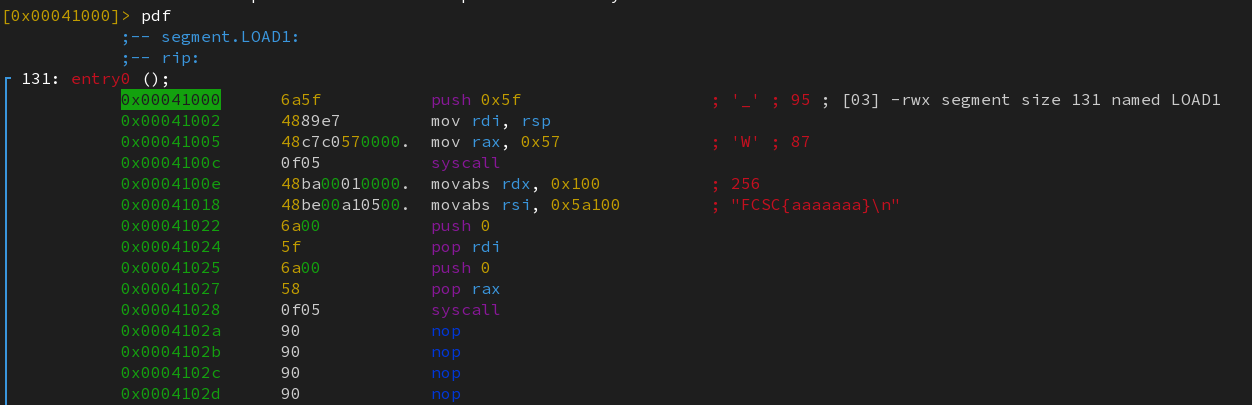

We find several of them : versions 151, 152, 4780, 4781, 6790, 6791. They go in pair because the initial jump mangling is reset every time. We can guess the use case for each pair : (151, 152) to display the welcome message, (4780,4781) to ask for user input, and (6790, 6791) to display the “Nope” message and exit.

Indeed, looking at versions 152 and 6791 unveils a write syscall (1).

Similarly, version 4780 makes a syscall to read (0).

In this last example, an interesting fact can be noticed : the user input is stored at address 0x5a100. Let’s see if any relocations make any use of this address…

Tracking down the user input

I made a script to dump the relocation table pointer at each version (not shown here, but you only have to dump the value located at address 0x420a0). Using this technique, two “loops” can be found : one of size 14 that starts at version 4787 and repeats for 70 times, and another one of size 13 and that repeats 70 times as well.

This value of 70 is interesting. The flag is expected to have the format FCSC{sha256 sum}. Given that a sha256 hash is 32-bytes long, or 64 hex digits long, and adding the 6 letters enclosing it, one can confidently guess that those loops iterate over the user input.

I encourage you to stop here and decode those instructions yourself, as I give minimal explanations in the next two sections.

First loop

The first thing to notice is the usage of another memory region located at 0x5a000 (called mask in what follows). This region contains fixed bytes that seem to have been chosen carefully.

a = mask[i+1]

index_b = (a + prev_index_b) & 0xff

b = mask[index_b]

swap mask[i+1] and mask[index_b]

offset = (a + b) & 0xff

user[i] = xor(user[i], mask[offset])

prev_index_b = index_b

with, initially, prev_index_b = 0.

Second loop

Similarly, it’s important to notice the usage of a secret string (of size 70 !) located at address 0x59132.

res = (user[i] + prev_res) & 0xff

res[i] ^ secret[i] ?== 0

prev_res = res

with, initially, prev_res = 0x25.

Cracking the code :smiling_imp:

Let’s now put everything together and crack this flag ! I went for a bruteforce method on every character of the flag.

from copy import copy

MASK = [0xf6,0xa0,0x62,0x98,0xcc,0x0f,0x19,0xf5,0xab,0x37,0xd5,

0x55,0xc9,0x5a,0x2b,0xb6,0x25,0xae,0x24,0x1d,0x95,0x9b,

0xfc,0xd9,0xa6,0xc3,0x7c,0x86,0x3b,0x4b,0xce,0xe7,0xb5,

0x42,0xb7,0xbb,0xb1,0x4c,0x29,0x73,0xc0,0x13,0x6a,0x40,

0x70,0x38,0x8c,0x61,0x93,0x68,0x0b,0xcf,0x07,0xc8,0x5f,

0xa3,0xb3,0xac,0x0a,0x90,0x53,0x7f,0xf0,0x48,0x3a,0x22,

0x58,0xb4,0xa2,0x46,0xc6,0x6e,0xa1,0xf7,0x12,0xca,0xec,

0x52,0x44,0x84,0x87,0x8a,0xba,0x8d,0xf4,0xfb,0x20,0x78,

0x4d,0xc2,0x67,0x9a,0x99,0x50,0x14,0x7a,0xe8,0xf2,0xf9,

0xd1,0x11,0x56,0x6f,0xb0,0x34,0x47,0x15,0xdb,0x00,0xee,

0x0e,0x06,0x18,0x88,0x10,0x79,0xd4,0x9f,0x9d,0x3f,0xad,

0x5d,0xa8,0xd3,0xf3,0x7e,0xde,0xcb,0x43,0xdf,0xbc,0x8b,

0xfd,0x03,0x1c,0x30,0xcd,0x01,0x91,0xd8,0x17,0x8f,0x64,

0xc7,0xeb,0xda,0x80,0xd6,0x6b,0x1a,0x3e,0x69,0xe6,0x60,

0xa4,0xff,0xed,0x35,0x6c,0x72,0x7d,0xc4,0x66,0x2d,0x21,

0x54,0x7b,0x33,0x1e,0x2e,0x26,0x75,0x59,0x57,0x94,0xb9,

0x5e,0x74,0xe0,0xc1,0x16,0x85,0xe9,0x96,0xc5,0xbe,0xdd,

0xa7,0xd0,0x32,0x0c,0x2f,0x65,0xd2,0x71,0x51,0x0d,0x82,

0xea,0xf1,0x05,0x4e,0x6d,0x83,0x31,0x02,0x2c,0x28,0xf8,

0x4f,0x49,0x23,0xfa,0x27,0xe3,0x81,0xaf,0x97,0xb2,0xb8,

0x41,0xe2,0x04,0x4a,0xe1,0x2a,0xe4,0xef,0x76,0x36,0x39,

0x92,0x63,0x3c,0x5c,0x5b,0xbf,0xdc,0x89,0x9c,0x8e,0xa9,

0x45,0xe5,0xd7,0x1f,0x9e,0x09,0xaa,0xfe,0xbd,0xa5,0x3d,

0x1b,0x08,0x77]

SECRET = [0x32,0x80,0x80,0x53,0x42,0x91,0x06,0x97,0x4f,0xce,0xdb,

0x9f,0x86,0x5e,0x82,0xef,0x89,0x6d,0x53,0x5a,0x68,0x39,

0x72,0x4d,0xe8,0xfc,0x2a,0x48,0xbc,0x09,0x98,0xa7,0x3f,

0xa5,0x6f,0xaf,0x5f,0x1c,0x9f,0xf1,0x76,0x76,0xdd,0xc1,

0xee,0x01,0x25,0x55,0xa1,0x2b,0x68,0x31,0x1a,0x31,0xa1,

0x45,0x05,0xe7,0xfd,0xde,0x75,0xb6,0xfd,0x71,0x8e,0x98,

0xcb,0xca,0xe8,0x61]

def compute_step(mask, prev_index_b, index, input):

a = mask[index+1]

index_b = (a + prev_index_b) & 0xff

b = mask[index_b]

mask[index+1], mask[index_b] = mask[index_b], mask[index+1]

offset = (a + b) & 0xff

input[index] ^= mask[offset]

return index_b

def compute_transformation(input, steps):

mask = copy(MASK)

prev_index_b = 0

for index in range(steps):

prev_index_b = compute_step(mask, prev_index_b, index, input)

return mask

def check_char(prev_res, index, input):

res = (prev_res + input[index]) & 0xff

return (res, res == SECRET[index])

def crack_passwd():

input = bytearray(b'\x00'*256)

prev_res = 0x25

for index in range(70):

for i in range(255):

curr_input = copy(input)

mask = compute_transformation(curr_input, 70)

prev_res_new, valid = check_char(prev_res, index, curr_input)

if valid:

prev_res = prev_res_new

print(f"Cracked character {index} : {input[index]}")

break

if i==255:

print("uh oh")

input[index] += 1

return input

print(crack_passwd())

Output :

Cracked character 0 : 70

Cracked character 1 : 67

Cracked character 2 : 83

Cracked character 3 : 67

Cracked character 4 : 123

Cracked character 5 : 49

Cracked character 6 : 54

Cracked character 7 : 50

Cracked character 8 : 55

Cracked character 9 : 53

Cracked character 10 : 54

Cracked character 11 : 56

Cracked character 12 : 50

Cracked character 13 : 56

Cracked character 14 : 51

Cracked character 15 : 49

Cracked character 16 : 50

Cracked character 17 : 97

Cracked character 18 : 97

Cracked character 19 : 100

Cracked character 20 : 53

Cracked character 21 : 54

Cracked character 22 : 50

Cracked character 23 : 51

Cracked character 24 : 57

Cracked character 25 : 52

Cracked character 26 : 100

Cracked character 27 : 52

Cracked character 28 : 55

Cracked character 29 : 99

Cracked character 30 : 56

Cracked character 31 : 53

Cracked character 32 : 52

Cracked character 33 : 49

Cracked character 34 : 51

Cracked character 35 : 52

Cracked character 36 : 56

Cracked character 37 : 48

Cracked character 38 : 51

Cracked character 39 : 97

Cracked character 40 : 48

Cracked character 41 : 57

Cracked character 42 : 50

Cracked character 43 : 100

Cracked character 44 : 55

Cracked character 45 : 102

Cracked character 46 : 53

Cracked character 47 : 98

Cracked character 48 : 57

Cracked character 49 : 101

Cracked character 50 : 98

Cracked character 51 : 55

Cracked character 52 : 57

Cracked character 53 : 53

Cracked character 54 : 53

Cracked character 55 : 50

Cracked character 56 : 56

Cracked character 57 : 102

Cracked character 58 : 52

Cracked character 59 : 97

Cracked character 60 : 48

Cracked character 61 : 102

Cracked character 62 : 49

Cracked character 63 : 54

Cracked character 64 : 102

Cracked character 65 : 55

Cracked character 66 : 99

Cracked character 67 : 54

Cracked character 68 : 53

Cracked character 69 : 125

bytearray(b'FCSC{162756828312aad562394d47c854134803a092d7f5b9eb795528f4a0f16f7c65}\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00')

Congratulations, you are now a dark elf magician !